MEET OUR LAB

Every once in a while I get emails asking about the type of research I do. I started working with bacterial genetics when I was only 20 years old in a lab in Sao Paulo during my college years, then worked at Stanford on biotechnology of vaccines, a very exciting period in my professional life, and the beginning of me falling in love with beautiful California. Went back to Brazil, had my own lab for a few years, left to work at Institut Pasteur in France, where I met the scientist who years later would become my husband. We’ve been working as a team for over 20 years now, trying to figure out the mechanism of a transport reaction in bacteria.

We study how bacteria such as Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes get iron from the environment and “swallow it up.” The metal is indispensable for bacteria as well as all other living organisms to survive, but it is very tricky to obtain. Iron can be compared to money in the sense that everyone who has it tries to protect it from being taken away. However, bacteria developed sophisticated systems to do just that: steal the iron from you and use it to survive. Since all pathogenic bacteria need to obtain iron to cause disease, we hope that our research will lead to the discovery of new weapons to fight infections.

If you want to read more about it, visit our lab website, still under construction, but already in good enough shape to give you a general idea of what we do.

Here at UCLA we are studying a different transport system, that allows bacteria to take up a sugar called lactose. A lot of what we are learning in this system will help our own research in Oklahoma in the future.

ANTIBIOTICS AND FOOD

If I were to define myself professionally, I’d say I am equal parts microbiologist, molecular biologist, and biochemist. I obtained my doctorate in biochemistry in 1986, working on the genetic instability and antibiotic resistance of bacteria. Since then, I’ve studied bacterial pathogenesis, vaccine biotechnology, and more recently, the biochemistry of iron uptake by Escherichia coli and Listeria monocytogenes, two potentially lethal bacterial contaminants of food. As a result of these experiences, I have strong opinions about the use of antibiotics in food production.

Watching the news this week, I saw a pig farmer from my home state (Oklahoma) defending the practice of feeding pigs antibiotics to improve their health and weight. I’d love nothing better than to invite that man over for a cup of coffee and a conversation, so I could ask him what exactly he knows about the use of antibiotics. For example, has he ever heard of the term “plasmid?”

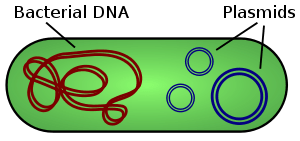

Bacteria possess efficient and sophisticated responses that block antibiotic action, which existed long before we “discovered” them (in 1929), before we learned to produce them (in 1943), and before we created new, more potent derivatives, sometimes with a broader spectrum of microbial targets. Just like any living organism, bacteria organize their DNA in a chromosome, usually a single, large molecule that contains all the genes for survival and replication (in E.coli, that’s almost 4,500 genes). But, bacteria often possess additional DNA, much smaller and not part of the chromosome: this DNA is in the form of plasmids.

Keep in mind that the cartoon is not to scale: the chromosome is huge, and very tightly packed. Plasmids are a few thousand times smaller, but they may be present in high numbers, as much as hundreds of copies per cell. Plasmids usually contain genes that are not needed in “normal” situations, but are useful in adverse situations. Indeed, in the 1960’s scientists found that the genes that confer antibiotic resistance are often located on plasmids. This fact gives the microbes an added bonus, because plasmids may be transferred from one bacterium to another. A conjugative plasmid sends a copy of itself to other bacteria, in a very cool mating process. Yes, even these tiny unicellular creatures are into sexual activities, if the conditions are just right for it… 😉

Since the first antibiotic – penicillin – was discovered (in a very fortuitous way by Fleming), we’ve witnessed incessant evolution in the microbiological world: every new weapon designed by humans to eliminate bacteria is soon followed by the development of drug resistance, and as new resistance genes arise, they often associate together to form larger and larger plasmids, containing multiple drug resistance genes. You can read about a carefully studied example by clicking here.

At first, scientists were a bit puzzled by resistance genes ending up all neatly organized in plasmids, but later it became clear that these genes efficiently move among bacterial populations, literally “jumping around” from one place to another. They are classified as “transposons“, which gives an intuitive idea of what they do: they transpose themselves to new locations, while leaving the original copy of the antibiotic resistance gene in place.

Back to food. When farmers treat animals (like pigs) with antibiotics to produce more meat and “healthier” animals, they create strong selective pressure on the bacteria in the pig stomachs and on their skins, so that rare, antibiotic-resistant variants will arise, survive and take over the population. It’s only a matter of time. Many of these bacteria are potentially pathogenic in humans, and they will have plasmids that can be transmitted to other bacteria, including bacteria in the human digestive tract. So, even if the bacteria are themselves non-pathogenic, they may pass their antibiotic resistance to more harmful microbes by conjugation or other processes. Besides that, the antibiotics are eliminated in the animals waste, and end up permeating the soil, ultimately draining into rivers, lakes and reservoirs used for drinking water and irrigation of food crops in the surrounding regions. So the selective pressure for antibiotic resistance becomes ubiquitous, leading to the development of more and more dangerous bacterial strains.

Here’s some good news: the selective pressure works both ways. Carrying the extra DNA associated with plasmids is a heavy metabolic load for the bacterial cell. If you stop adding antibiotics to animal food, plasmid-free bacteria will have an advantage in growth and replication, and soon take over the population. The upshot of these explanations is clear: the less antibiotics that we use, in food production and in medicine, the better it is for the future of mankind.

Antibiotics as a preemptive measure in food production are unnecessary and driven by obsession with profit. This practice, that has undeniably caused infections in humans with microorganisms that are completely resistant to multiple drugs (click here for a very good article) was already banned in many European countries. Here in the US we witness a huge opposition to responsible action in the right direction. Why? In part because drug companies do not want to lose their profits from drug sales to the food industry. And in part because large-scale farming walks hand in hand with the pharmaceutical industry, hoping to raise their own profits by making meat artificially cheap, so that we eat lots and lots of it, even knowing that the practice is unhealthy. Ironically, if farmers stopped excessive antibiotic use, the price of pork would only increase by a meager 20 cents per pound. Twenty – cents – per – pound. Does that 20 cents a pound justify the threat of infections by antibiotic resistant bacteria?

Michael Pollan wrote two masterpieces on the subject of the American food industry. I highly recommend that if you haven’t read these books, do so as soon as possible. The bottom line is that by producing our food as cheaply as we possibly can, we are affecting the balance of our planet. We are raising cattle, pigs and chickens in horribly crowded conditions so that we can buy cheap meat, chickens for $3 per pound and eggs less than $3 per dozen. I do not advocate turning into vegetarians: my motto has always been “everything in moderation“. But, at some point, we need to stand up for what is right.

The practice of using antibiotics on healthy animals is irresponsible. Don’t let anyone fool you.

Morei no Canada antes de mudar para Oklahoma e duas semanas antes eu estava em Leduc, Alberta-Canada e ouvi que Alberta tomou a decisao de nao usar mais antibioticos para a carne de porco, eu particularmente estou evitando comer carnes, percebi que aqui em Oklahoma os alimentos contem mais gorduras e mais quimica em colorantes e preservantes, principalmente os derivados de leite, muito junk food e propaganda de remedios o que na minha opiniao e uma mistura perigosa!Obrigada por nos manter informados.

LikeLike

As I am studying natural medicine, and herbs as a way to health, I am so against antibiotics in livestock. Oprah did a show on this last week or the week before. 28 million lbs of antibiotics are given to animals raised for the table, PER YEAR! That’s via a man named Micheal Pollan, who has written several books. You’d think any idiot would know how bad this is, you would think…Yet when I tell people I don’t take antibiotics, but a silver compound called silver shield, I’ve been yelled at even, for not believing in antibiotics. That’s how programmed this country is to being addicted to doctors and pharmaceuticals. I don’t need healthcare, by the government or any other entity. I go the natural way.

LikeLike

Very nice web site my Portuguese sista!!!

LikeLike

Fascinating, and totally unexpected. I’m so glad I clicked the tab and read this. Thanks for sharing it and thanks so much for your lovely blog. Best wishes to you and yours. I hope your sabbatical exceeds all expectations.

LikeLike

Thank you for this information! And one thing I’m happy to see was the distinction between using antibiotics as a preventive vs in response to an infection. I have no problem with animals being treated if they are ill!

LikeLike

This makes for fascinating reading, as does the rest of your blog. I look forward to reading more…

LikeLike

Thank you! Hope you stick around and thanks for commenting!

LikeLike

My stepfather, David Parma, was I think one of the first to study E. coli. He’s dead, now. We used to have to mingle with some pretty interesting scientists growing up, including James Watson. Even babysat his kid! My mother was best friends with Barbara McClintock, who I think worked mostly on corn genetics. Anyway, I just found this page and thoroughly enjoyed it. Don’t understand all of it – I went the inorganic route and became a geologist!

LikeLike

Oh, how wonderful! We never met Watson, Phil met Crick, but not Watson. Now, Barbara McClintock has been an amazing source of inspiration for me from early on. Her biography, A Feeling for the Organism is a must read! She was ridiculed for her work and theories on corn genetics because they were too novel and hard to accept. The idea that genes could “move around” and that the DNA was not a “static” structure was too much at the time. My PhD work in Brazil had to do with genetic instability in bacteria and pretty much everything I worked on was a consequence of her work with corn. I am in complete awe that your Mom was best friends with her, complete awe!

LikeLike

My mother still talks about the impact that Barbara had on the world of science, but I had no idea. I was 12-13 when we lived in that biological science venue in Cold Spring Harbor, on Long Island, and I remember her well. We were the same size, for one thing, and she was quite the spitfire. I would have to traipse behind on many walks of theirs in the area – many through cornfields behind the labs! She had no interest in me, or any children. She really liked my mother because she was an academic “equal” – of course not along the same lines, but very intelligent and didn’t treat Barbara like the men did. Having been the only women in a world of men throughout my years as a geology major at school as well as working afterwards, and given the issues I dealt with, and these were the 70’s and 80’s, I can’t imagine what Barbara went through. There was a lot of jealousy, from what I remember my mother saying, as well. Men were very threatened. She probably would have been out of the closet, if she were living now. Or maybe not. I maybe shouldn’t say that. She was just such a little man! I wasn’t aware of her biography and I’m so glad you told me about it. I found a hardback online and I’m getting it for my mother for a birthday present. She’ll be thrilled. My father moved us to Utah, where he finished off his career at the U of Utah in salt lake city. My mother and Barbara never saw each other again, or even talked, from what I know. But I know that Barbara still holds a special place in my mother’s heart.

LikeLike

You and your Mother will love her biography, I am sure of that. Interesting that you mentioned the “out of the closet” bit. It was something I wondered after reading her book, she passed this aura of complete “non-sexuality”, as if her life was all about research. It is clear to me that only a person with very strong personality could endure what she did – and yes, I always thought it was also interesting that she was “petite”, probably exactly my height, or an inch or so taller than me (it is hard to beat me, you know.. 😉

so glad you commented on this old page! I should write more often about our research, but life is busy and I keep postponing it and postponing it

LikeLike

Hello Sally! I found your blog through Emily (Life on Food) today for SRC. I am a PhD student in neuroscience and I blog as well! It’s so great to see that PIs also have a passion for blogging and cooking! I’m a new follower 🙂

LikeLike

Neuroscience! That is absolutely awesome! If I had to start all over, that would be an area I would love to work on… you know “promote myself” from prokaryotes to eukaryotes.. Maybe next life though — So glad you found my blog! I will be jumping to visit yours!

LikeLike

Pingback: The Ultimate Apple Spice Cake — Shockingly Delicious

Pingback: Linzer Cookies | Butter Basil and Breadcrumbs

Fantástico e importante o seu trabalho, Sally!!! Parabéns!!!

LikeLike

Thank you for this summary and explanation of the cause of antibiotic resistant bacteria. I will pass this on to friends.

LikeLike

Hello, I ended up here because I just started reading Baking Chez Moi and then wanted to read some reviews and read yours. I then read your about and was fascinated with the lived in Paris and your education and career. I am utterly amazed at what is permitted to be sold as food in this country and how the food is altered. I will be back to read more. Bon nuit.

LikeLike

Welcome to my blog! Glad you enjoyed what you’ve found here so far, and I hope you stick around… 😉 Thanks for the nice comment!

LikeLike

Being that my PhD work was on C. albicans and it’s resistance mechanisms to antifungals I definitely share some of the same passions (and found some interested results involving iron as well). I love finding out that other bloggers who are scientists!

LikeLike

Awesome!!!!! Iron is great!

LikeLike

Hi YASHASWINI here, went through your Blog, amazing & mouth-watering recipes.

People like you are an inspiration for an amateur blogger like me. Would you kindly spare your valuable time in going through my Blog (https://yashaswinibs.wordpress.com/) and provide feedback. Thanks in advance.

LikeLike